Chiura Obata: Alien Enemy and Great American Painter

Chiura Obata applied Japanese training and technique to picturesque California landscapes with stunning results. Interned during World War II because...

Theodore Carter 19 May 2025

John Singer Sargent’s flattering, flashy images of late Victorian and Edwardian high society are justifiably famous. They made him rich but they didn’t necessarily keep him artistically satisfied. Sargent was a chameleon and an enigma: at home everywhere, working in different media, adopting new styles and yet never revealing himself. These 10 paintings highlight the diversity and brilliance of his artistic vision.

John Singer Sargent, En route pour la pêche (Setting Out to Fish), 1878, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

Born in Florence to expatriate Americans, John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) spent his childhood in Europe and gravitated toward Paris to learn his art. He studied with Carolus-Duran, a portraitist best known for his teaching, but was also influenced by French landscapists like Eugène Boudin and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, who were developing a looser, lighter style.

In 1877, he spent time sketching outdoors at Cancale on the Brittany coast. En route pour la pêche (Setting Out to Fish), exhibited at the Salon and immediately bought by an American collector, was the result. Breezy, atmospheric, and luminous, the sky takes up almost half the canvas, with its blues and whites further reflected in the pools on the beach.

Despite the sense of spontaneity, it is carefully composed with the lighthouse creating a starting point for an arc of figures which emerge from the distance towards the central group. There is a deliberate mix of ages; the central figure draws our eye with her red hair and red underskirt; the baskets form a repeated motif. Cleverly composed casualness became a recurring feature of Sargent’s art.

John Singer Sargent, A Street in Venice, c. 1880–1882, Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, USA.

In 1880, Sargent visited Venice, seeking out not the tourist hot spots but dingy back alleys and working life. His choice of bead stringers, glass workers, and onion sellers, like that of the oyster gatherers at Cancale, can be seen in terms of the French Realist tradition with which he would be familiar. Carolus-Duran had been influenced by Gustave Courbet in his early career and was friends with Édouard Manet.

Sargent does not shy away from poverty, and his grimy, almost monochrome palette is reminiscent of works like Manet’s The Absinthe Drinker (c. 1859). A Street in Venice has none of the sunshine associated with the so-called “city of light,” and its claustrophobic tunnel perspective is emphasized by crumbling plasterwork. There is an unsettling, ambiguous narrative between the two figures.

However, Sargent devotes as much energy to the complex, layered brushwork and color on the woman’s tattered, pink skirt as he later would to fine satins on society beauties. It suggests that he is less interested in making a social point about poverty and more about exploring the aesthetic possibilities of the scene.

John Singer Sargent, An Out-of-Doors Study (Paul Helleu Sketching with His Wife), 1889, Brooklyn Museum, New York City, NY, USA.

In Paris, Sargent also became friends with leading Impressionists like Claude Monet: he bought some of his works and painted him working outside in 1888. Sargent sympathized with the group’s aims to modernize art, and superficially, there seems to be a similarity between his loose style and the Impressionists’ lack of finish. Like them, he sketched outdoors and produced landscapes. However, Sargent never participated in the Impressionist exhibitions, and he was never as interested in prismatic color and light as the French painters.

His portrait of Paul Helleu, a pastel specialist whom Sargent first met as a student, shows a more markedly impressionistic style with its small dashed strokes, lightened palette, and color variations in the grass, not to mention its determinedly plein-air title. However, it is the composition that is most striking. A series of contradictory angles—canoe, fishing rod, canvas, hats—and a downward viewpoint which excludes the horizon and obscures the faces, create an awkward and very modern lack of focus.

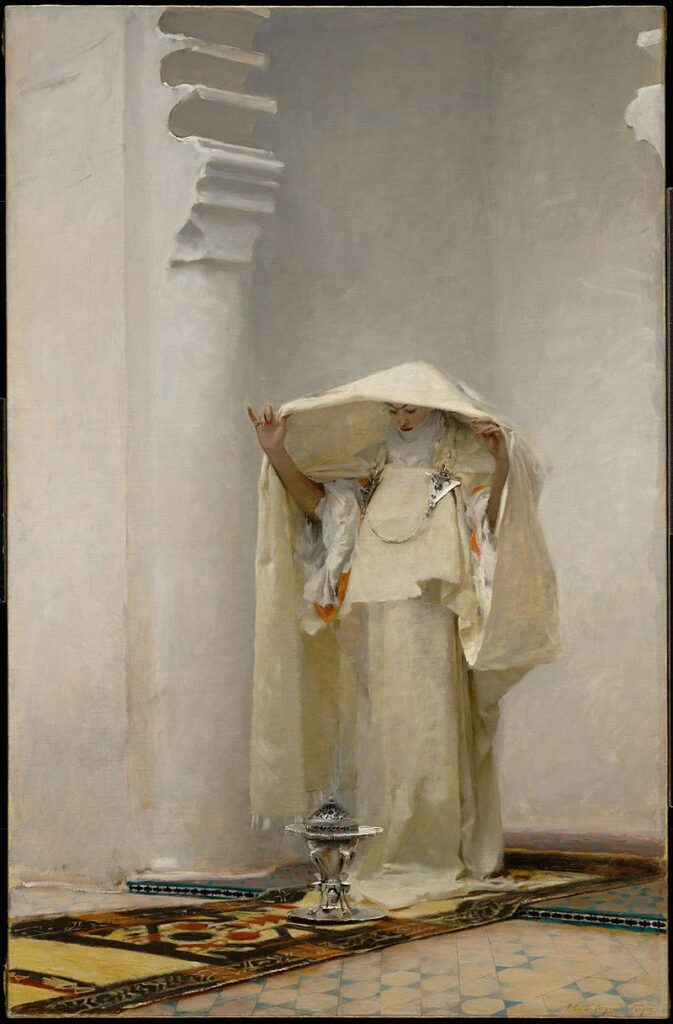

John Singer Sargent, Fumée d’ambre gris (Smoke of Ambergris), 1880, Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, USA.

The most significant difference between Sargent and the Impressionists lays in his enthusiasm for black and white. Famously, while visiting Giverny, France, he asked for black paint and was appalled to be told that Monet did not own any. Fumée d’ambre gris, a work inspired by a visit to Tangiers in North Africa, is almost entirely painted in shades of white. On the one hand, it is a sensual piece of Orientalism: a woman covers her head to better inhale an aphrodisiac incense. The architecture and patterned rug clearly locate the scene outside Europe.

However, the painting can also be read in terms of the work of James McNeill Whistler, a fellow (although older) expat portraitist, whom Sargent had first met in Venice. Fumée d’ambre gris (Smoke of Ambergris) shares Whistler’s enthusiasm for a tonally limited palette and Ambergris references his Symphonies in White, which similarly feature female figures in an exploration of a single color.

John Singer Sargent, El Jaleo, 1882, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, MA, USA.

Sargent visited Spain on his journey to North Africa, driven by an enthusiasm for Diego Velázquez, another legacy of his teacher, Carolus-Duran. Previously, along with Helleu, he had made a similar pilgrimage to the Netherlands to see the work of Frans Hals, the 17th-century portraitist. Hals was famous for, as Vincent van Gogh wrote, his “27 shades of black” and his dashing brushwork. El Jaleo channels both these artists with its modern take on a traditional genre subject.

Sargent is again working in near-monochrome with the flash of a red right on the extreme right and the orange on the empty chair, injecting the only warmth. The plain background and shallow picture space bring us close to the action, and especially the sound of guitars and flamenco heels. Equally, the repeated musicians lined up in their chairs and the vertical of the hanging guitar serve to emphasize the dramatic leaning pose of the dancer and the swirl of her costume.

The scale, over three meters (130 in.) across, and theatricality of El Jaleo are a statement of Sargent’s artistic confidence. The same bravado would cause him trouble two years later when his portrait of Madame X became so notorious that he chose to leave Paris for London.

John Singer Sargent, Dr. Pozzi at Home, 1881, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

If Fumée d’ambre gris was a study of whites, Dr. Pozzi at Home is an exploration of red. Samuel Pozzi was a French gynecologist, so well known as a womanizer that his nickname was Dr. Love. Sargent chose to show him, not professionally suited, but in his dressing gown, with white frilled collar and cuffs, making him look almost like a disreputable Renaissance cardinal. The elegant beard, elongated fingers that gently fondle the fabric, and dazzling eyes give him a red-hot, devilish charm.

Sargent never married; he kept his private life private, and there has been much speculation about his sexuality. Whether he viewed Pozzi and others with a gay male gaze, or whether Sargent just liked an element of theatricality in his portraits, we will never know. However, Dr. Pozzi’s character is as defined by his clothes as much as any of Sargent’s women, and the same can be said of W. Graham Robertson in his oversized overcoat or Lord Ribblesdale strutting his stuff in riding boots and top hat.

John Singer Sargent, Mrs. Hugh Hammersley, 1892, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

Sargent’s representation of women was equally nuanced. He was certainly a flatterer, or he would not have been such a popular choice among the rich and famous of the period. As a recent exhibition at Tate Britain demonstrated, he also loved fashion and was a brilliant painter of fabric. However, Sargent never treated his female sitters as mere clothes-horses. His women have depth and character.

The luscious velvet of Mrs. Hugh Hammersley’s pink dress with its glistening lace trim gives the painting a Rococo prettiness which Sargent runs with. He picks up the same rosy reds in the rug and surrounds the figure with cream and gold furnishings. It suits the lady’s petite, almost doll-like proportions. However, her pose, perched on the front of the sofa, almost about to rise, with her left hand braced against its back, suggests dynamism and action. Her mouth, slightly open with teeth visible, is about to welcome us with a smile. She looks interested and interesting, with bright eyes and a swirl of messy hair like a metaphor for her active mind.

John Singer Sargent, Cashmere, 1908, private collection. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Sargent grew increasingly tired of the treadmill of his life as a successful portrait painter. The period after 1900 saw him retreat into watercolors, landscapes, and subjects chosen simply to please himself, experiment with, and explore aesthetic ideas. Cashmere was painted when he was on holiday in the Italian Alps, but it is not linked to a specific place, time, or even subject.

Seven different versions of a female figure draped in a cashmere shawl wander across an almost featureless background. It seems likely they were all modeled on Sargent’s 11-year-old niece, Reine Ormond, who was staying with him. Perhaps it was an attempt to explore movement as he effectively shows her in the act of walking, rather like a painted version of Eadweard Muybridge’s photographs.

However, the title is sensual, suggesting the softness and warmth of the luxury fabric, and the shawl was repeated by Sargent in paintings like Nonchaloir. Equally, the mood generated, especially by the two figures who look out of the canvas, is wistful. Like Albert Moore before him, Sargent is using color, sensation, and female beauty to create an image of pure aesthetic pleasure.

John Singer Sargent, The Chess Game, c. 1907, private collection. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

There is an infectious exuberance about Sargent’s early 20th-century landscapes, as if he were a man at ease with himself and with nothing left to prove. These are small-scale, intimate corners of nature, usually painted on the spot, often including family and friends. The Chess Game is typical with its downward angled perspective, which ignores the sky completely, and exaggeratedly casual poses with figures sprawling on the grass, almost indistinguishable from the nature around them.

Water is often featured, adding movement and sound. The light, bright pastel shades focus on pinks and creams, dappling color across the canvas so that even blues and greens are given added warmth. The paint surface is completely disrupted, sweeping brushstrokes which merge forms together almost to the point of semi-abstraction. The result is idealized, exoticized, and highly sensual as if Sargent is turning his flatterer’s eye on Nature itself. Beauty and life are everywhere.

John Singer Sargent, Gassed, 1919, Imperial War Museum, London, UK.

The First World War caught up with Sargent. In August 1914, on another endless sketching trip, he was trapped in the Austrian Tyrol, unable to return home for months. His beloved niece, Reine’s sister, Rose-Marie Ormond, was killed working as a nurse, as was her husband. Aged 62, Sargent himself spent four months at the Front as an official war artist.

The result was Gassed. A huge, six-meter-long frieze of horror as men, blinded by a gas attack, stumble across a desolate landscape piled high with their wounded comrades. The only respite is a game of football taking place in the distance. Sargent has stripped everything back. Color, brushwork, and clever composition are all unnecessary in the face of such horror.

John Singer Sargent was right at the end of his career, but still proving that he was an artist who could turn his hand to everything.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!